“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

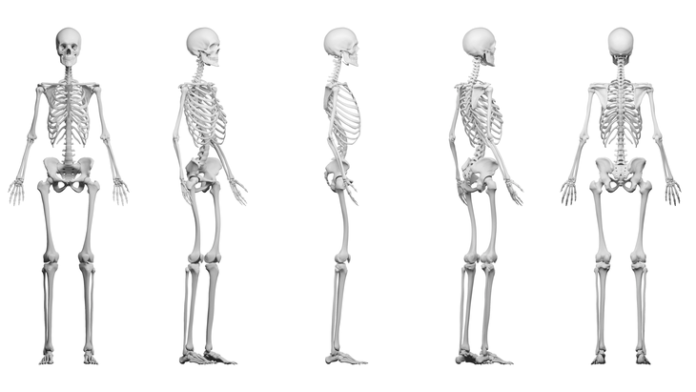

There’s a fundamental anatomical truth that affects almost every yoga pose you practice. And it’s rarely explained or even acknowledged in most classes.

Every single person practicing yoga has different body proportions. Known as variable anatomy, this fact essentially means some bodies are going to be able to do some poses more easily than others.

Rock climbers understand this. They know to take into consideration the length of their legs in relation to the length of their arms. It allows them to have a better understanding of what they can and cannot reach.

What does this mean for yoga shapes? Well, standing and lifting one leg straight in front of you and not being able to reach your hand to your big toe doesn’t always mean that you have tight hamstrings. If you have shorter arms and longer legs, you ain’t grabbing no toes.

The same principle applies when you reach your hand to your foot in Happy Baby or step your foot forward from Three-Legged Dog to the front of the mat. Each of these is massively more challenging if you have shorter arms.

Almost every shape you can make in yoga is affected by your anatomy, including touching your hand to the mat in Extended Side Angle or Triangle. And if you’re attempting Bird of Paradise, you can have the most open shoulders in the world, but if your arms aren’t a certain length, you will experience problems binding your hands behind your back.

Why Variable Anatomy Makes All the Difference

We hear a lot in yoga about how the practice is for “every body.” But with variable anatomy, there are many yoga shapes that are literally impossible for some. This approach isn’t defeatist. It’s an acknowledgement of skeletal limitations and a reminder to question the unnecessary elitism around coming into shapes in yoga.

As a yoga teacher, I continue to witness how understanding the most basic definition of variable anatomy has affirmed people in their own physical bodies.

One student explained that she’d been working on the shape where you sit with your legs straight in front of you in Staff Pose, place your hands along your sides, and push down to lift your bum off the mat. She’d been trying to do that for 15 years. But she couldn’t get her hands on the floor.

In order to place her hands flat, she had to lean forward and place her hands closer to her knees rather than her hips, which in turn caused her to contract her abdominal muscles and fold forward. That means she had to draw on core strength to pull herself forward. For her to then lift her bum off the floor, she would need to draw more on her core strength than someone who happens to have long arms.

But no one had ever told her that it was because of her anatomy. At any point during those 15 years, a teacher could have placed a block on either side of her to lift the ground to her hands and she would have been able to find the shape without nearly as much stress.

Learning this changed her story about how everyone else’s practice was better than hers.

How to Teach Variable Anatomy

I think a lot of us see a shape as a test and feel shame if we sense we have failed it. Variable anatomy reminds us that we don’t need to be able to do every posture to find value in our practice. It’s a liberating thing to understand.

As teachers, we can—and should—explain variable anatomy and be able to adapt the shape to students rather than continue with the ridiculous expectation that with enough effort or practice, everyone can overcome their anatomy and make a shape in the same way.

When students begin to see shapes not with shame at what they’ve been told are tight hamstrings or a lack of trying but with the understanding that the postures demand proportions that perhaps aren’t built into their anatomy, hey begin to think, “Alright, well, I’m going to use a strap. And that’s okay.”

When you explain the role of the skeleton, people feel liberated in their own physical body. They feel affirmed about who they are rather than feeling inadequate. That creates an entirely different experience of yoga in which you begin to shatter the false narrative that being able to do a shape means you’re “good” or “advanced” in yoga.

As teachers, we don’t have unlimited time to talk in class and explain concepts, so it can become a little tricky to drop in, but there are concise insights that you can share when you’re cueing. Perhaps something like, “Some of you might be able to reach your foot. If you can’t, it might have something to do with tension in your body or it could just be the length of your arm.”

The more relief I see on students’ faces when I share this information, the more I realize how important it is for everyone to understand this truth.

Of course, some students do have tight hamstrings that can be coaxed and stretched with practice. But it’s still critical to remember that not every body is built for the traditional shapes in yoga. The responsibility lies instead on us to shift the way practice is taught and shared.